New laws reflect states’ move to consolidate early learning and care

Goal is to end fragmented system, better integrate programs that serve families and providers

For years, a common target of government reform advocates has been “siloing,” when a lack of inter-agency planning and communication results in redundancies and inefficiencies, as well as frustration among citizens.

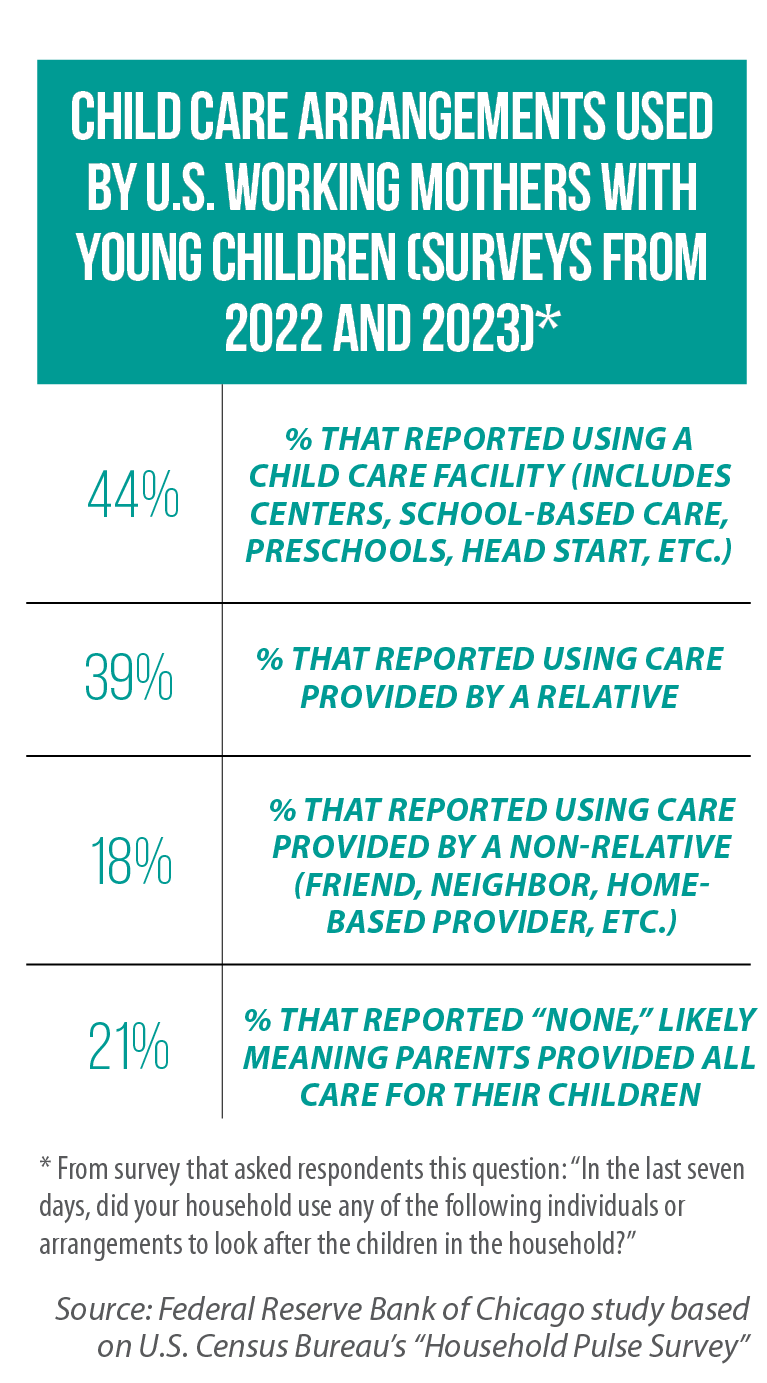

A case in point: an often-fractured approach to delivering and overseeing the services that the families of young children need.

“Right now, if a day care center wants to set up shop, it must work with one state agency to get licensed, another to receive workforce support, and a third to get funding,” Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly said in her State of the State address at the start of the year.

“There are too many barriers, too many portals, too much hassle. We need to fix it.”

Other policy leaders have observed similar governance problems in their states, at a time when they are looking to expand the capacity and quality of early-childhood care and learning opportunities — a policy goal that has been identified as crucial to addressing everything from workforce shortages to young people’s readiness for K-12 success.

“Families are not getting the services that they need because they are not sure where to go to or what they’re entitled to,” says Illinois Rep. Joyce Mason, chair of the House Child Care Accessibility & Early Childhood Education Committee.

In her state, and across much of the region, a push is under way to end the siloing and create a governance model that works better for families, early-childhood providers and other stakeholders.

The result has been a mix of executive actions by governors, legislative proposals and laws, many of which are creating new stand-alone state agencies that consolidate programming and regulatory oversight of early-childhood education.

States creating new stand-alone agencies

Last year, Minnesota legislators (as part of a larger effort to break up certain divisions within the Department of Human Services) created the Department of Children, Youth and Families (SF 2995).

According to the Minnesota Star Tribune, in addition to gaining administrative authority over child care licensing and certain early-childhood education programs, the department will oversee foster care and adoption programs and the juvenile justice system.

More broadly, it will improve the coordination of services while “elevating children and families in policy and budget decisions,” according to a March 2024 report from Minnesota Management and Budget.

In Michigan, the Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement and Potential was established in July 2023 with the signing of an executive order by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

As the department’s name suggests, its work is not just limited to early childhood education and child care programming. Mobilizing and delivering education resources for all ages, from preschool to postsecondary and beyond, falls under its mission.

“If we’re recruiting adults to come back to school under programs like Michigan Reconnect, what are we doing at the same time about [their] children who count on them for caregiving?” says Michelle Richard, deputy director of higher education for the new department.

Having all of those services housed within a single agency, she adds, better reflects how people’s lives intersect with the work of multiple state programs.

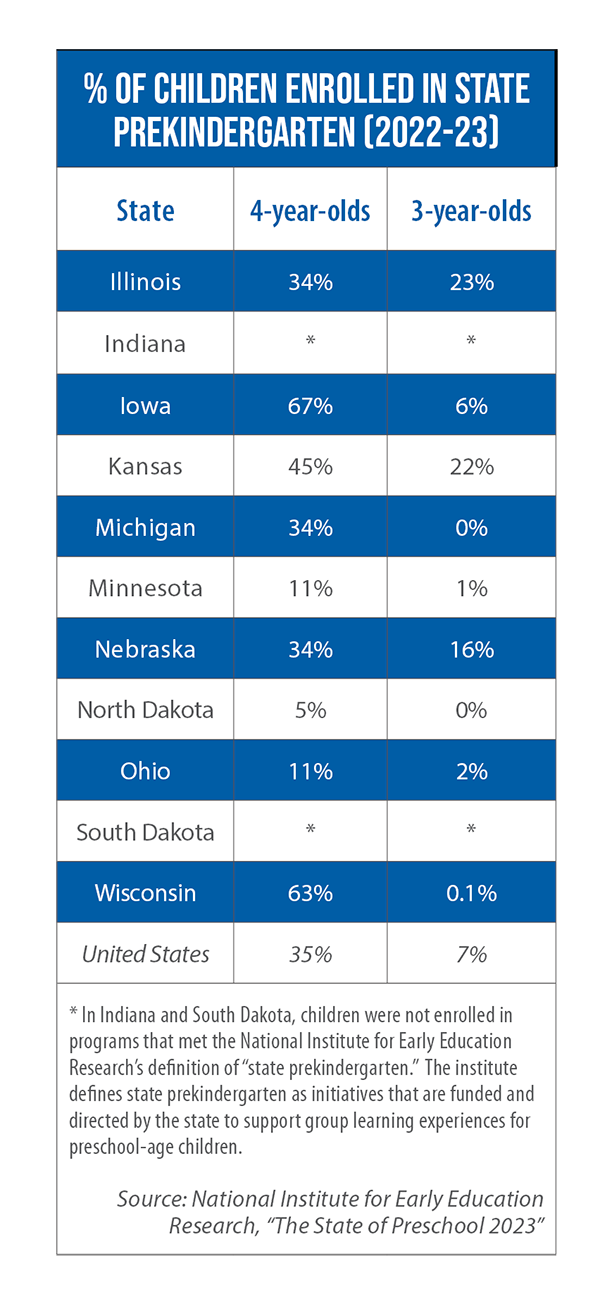

This administrative consolidation, Richard adds, should help the state as it seeks to fund universal prekindergarten for all 4-year-olds by 2027. Advocates in Illinois have articulated a similar 2027 goal.

“When we’re thinking about that planning work here [at the department], we’re not thinking about, ‘Our pre-K team needs to lead this work,’ ” Richard explains.

“Maybe that’s true, but they need to be surrounded by a team that says, ‘If we do this, what does that mean for child care? If we do this, how are we collaborating with Head Start? How are we using child care licensing rules to help jump-start pre-K classrooms?’ ”

‘Smart Start’ in Illinois

Michigan’s change in governance is somewhat unique compared to other states in the region.

Administrative consolidation came about in less than five months and was purely the result of an executive order. (Note: The constitutionality of this order has been questioned by some opponents, particularly as it pertains to the authority and duties of the State Board of Education.)

In contrast, advocates in Illinois and Kansas called for a two-year transition period, and the governors sought consolidation through legislative action.

And in both of these states, calls for new stand-alone agencies came as the result of findings from bipartisan task forces.

Between 2019 and 2021, a governor-established commission in Illinois focused on ideas for ensuring equitable funding and outcomes for children during the pivotal early learning years.

The commission noted in its final report that the state had a long way to go to reach these policy goals. For example, it found that kindergarten readiness varied distinctly across racial and ethnic lines.

The report also stated that in 2019, “only 20 percent of low-income children and 29 percent of all Illinois children demonstrated full readiness across language/literacy, math, and social-emotional domains when they entered kindergarten.”

Gov. JB Pritzker and legislators have since launched a multi-year appropriations plan known as “Smart Start.” Along with more funding for home visiting programs, Smart Start grants are used to increase wages in the child care sector and to add preschool seats in Illinois communities identified as “preschool deserts.”

The commission’s final report also proposed the creation of a Department of Early Childhood. Pritzker embraced the idea and passed an executive order to kick-start work on the transition.

He sought legislative action as well, and SB 1 became law in June.

Rep. Mason, one of the bill’s chief co-sponsors, says that in addition to helping families navigate and find the early-childhood services available to them, the new department will allow existing state agencies to prioritize their core missions.

For example, child care licensing authority is being taken away from the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, an agency that has often faced bipartisan scrutiny over child safety and neglect-related deaths.

Removing this authority from DCFS will not only mean more of a focus on child well-being within that agency, Mason says, but also an opportunity for the state to modernize licensing in child care.

“If you are going to work in an early-childhood center and you are going to make, say, $17 an hour, and now you’re being told you have to wait up to two months for us to get the background check back … that’s not realistic, because the next day you could get hired at Target for the same or more money,” Mason says.

More community outreach

This recent focus on governance issues in early childhood also has led to other proposals in Illinois.

Rep. Jackie Haas has been part of a working group in her caucus looking at ways to make it easier for women to become the owners of child care businesses and to fill needs in their communities.

“What we were hearing from some of our constituents [and chambers of commerce] was they didn’t know how to open up their own centers,” says Haas.

“[DCFS holds] all of the orientations in field office sites, and they’re all in-person, with no virtual training. We looked at how we could possibly expand where they’re doing these so that it would cover more geography in the state.”

These conversations led Haas to sponsor HB 4059, which was signed into law in August and requires the state to hold orientations at least twice a year, offer virtual meeting options, and make them made available in languages other than English.

Regarding SB 1 and creation of the new stand-alone agency, Haas says she is optimistic that it could lead to “some strides for improvement in early childhood education.”

But she also believes policymakers should critically evaluate the eventual size of the department’s workforce “before we look at completely lateral transfers.”

Mason and other SB 1 supporters have made clear the intent is for no state employees to lose their jobs at the end of the transition period. For positions that are deemed redundant, Mason says, the plan will be to retrain people and perhaps rotate out some staff currently working in high-turnover divisions, such as casework.

GG Weisenfeld of the National Institute for Early Education Research says one caveat about agency consolidation is that the end result is not always a leaner workforce or completely streamlined operations.

“People have the assumption, ‘Oh, if I just consolidate programs, I can get rid of people’, and you really can’t,” Weisenfeld says.

“You still need people to run programs, you need people to coordinate, you need people to figure out how all these funding streams are going to blend in or braid.”

‘Over 900 slots short’

Last year, Gov. Kelly created the Kansas Early Childhood Transition Task Force, whose work and findings led to her proposed Office of Early Childhood.

Despite Kansas being the first state in the country to create a Children’s Trust Fund way back in 1980, the task force (using data from 2018 to 2020) found that 44 percent of the state’s residents live in a child care desert, only 8 percent of families can afford infant care, and 38 percent of 3- to 5-year olds are not enrolled in a pre-K program.

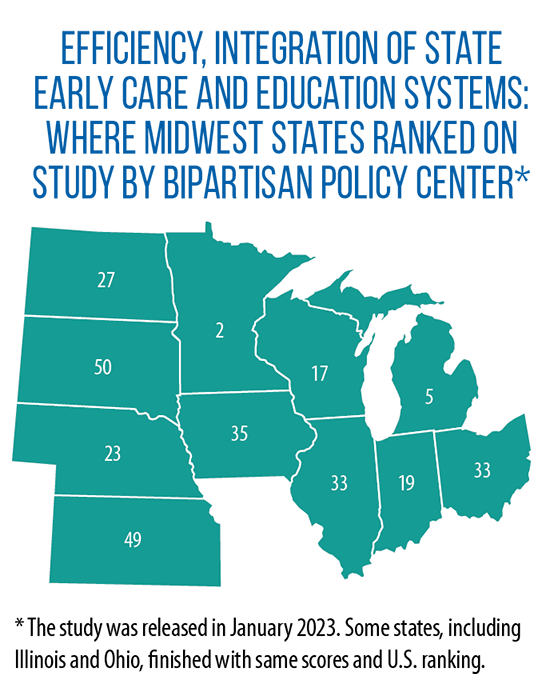

Additionally, a 2023 report from the Bipartisan Policy Center ranked Kansas 49th among states in a study assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of coordination of state early childhood systems.

Throughout the spring session, plans for this new Office of Early Childhood evolved several times before culminating in the language of SB 96. When this bill entered conference committee for amendments, Rep. Tory Marie Blew became one of the chief negotiators.

Like the governor, Blew believes having a one-stop shop for early-childhood education could lead to better coordination. However, that doesn’t mean the Legislature and the governor’s office were in complete lockstep.

For example, one sticking point was whether to provide more flexibility to child care centers on their staff-pupil ratios.

Republican lawmakers, who favor increasing ratios for certain age groups, argue it could open more slots in child care centers and thereby expand access.

“Just in my county alone, which is a rural county, we’re over 900 slots short,” Blew says.

Kelly, a Democrat, and others argued that increasing the number of children or infants per staffer could jeopardize safety.

The compromise: Any increases to staff-pupil ratios would need to come via administrative rulemaking, not a change in statute.

Other notable changes made in conference committee included allowing non-family members to watch children for longer periods of time, expanding the definition of “day care facility” to include youth out-of-school or “drop-in” programs, and the formation of a five-year pilot program to waive certain licensing requirements and to increase child care facility and drop-in program capacities.

SB 96 did not receive a final vote in the Senate before legislators adjourned.

The overarching idea of having a stand-alone agency for early childhood, though, remains a top priority of Kelly’s. It likely will be considered again next session.