Require paid sick leave for workers? Nebraskans said ‘yes’ on a recent ballot measure; changes also are coming soon to a 6-year-old Michigan law

This past November, a total of six ballot measures were decided on by voters in Nebraska.

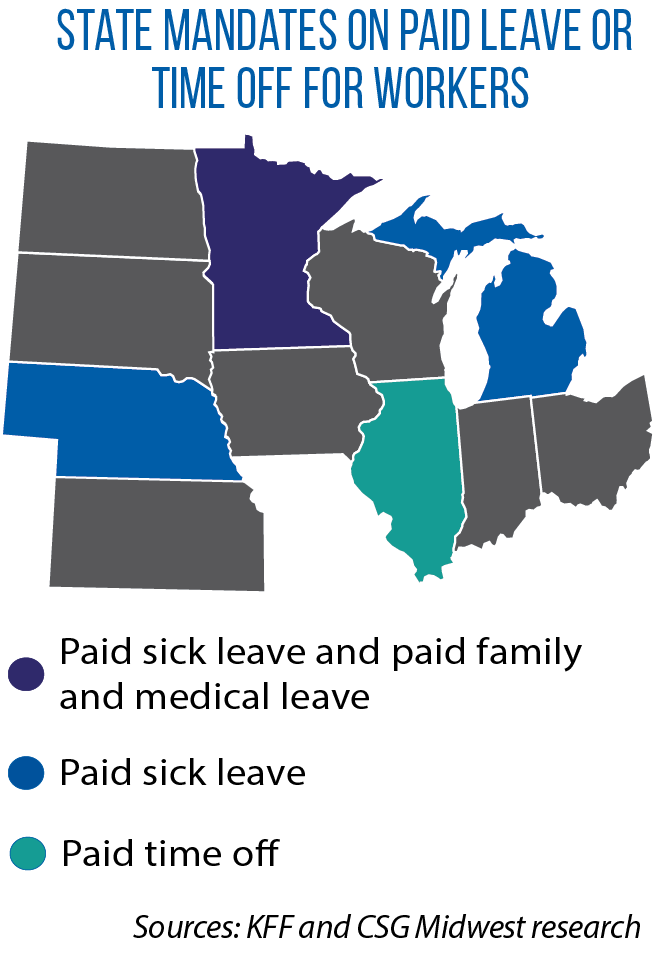

The one that received the most widespread support: a new requirement that workers in the state have access to paid sick leave. Seventy-five percent of Nebraskans voted for the proposal, a higher margin compared to results reported in the two other states with similar ballot initiatives in 2024, Alaska and Missouri. (The measures passed in these two states as well.) Nebraska now joins Illinois, Michigan and Minnesota as the Midwestern states with these kinds of laws in place.

From stalled legislation to ballot win in Nebraska

Beginning in October, Nebraskans working at a small business (fewer than 20 employees) will be able to accrue at least five days of paid leave in a year. Employees at larger businesses can earn at least seven.

Individuals who work less than 80 hours in a calendar year are not covered. The law also does not apply to federal railway workers and federal or state employees.

Nebraska Sen. Tony Vargas, a supporter of the new law, recalls when his parents had jobs that didn’t provide paid sick leave and, as a result, faced decisions on whether they could attend to a loved one’s health (or their own).

When they did have benefits, he says, the decision-making process changed to, “What was best for the family, not what can we afford to do right now?”

Vargas had attempted to get a bill through Nebraska’s Unicameral Legislature. His 2021 measure (LB 258) called for nongovernmental employers who hire four or more people to provide workers with at least 40 hours of leave in a calendar year.

Vargas says he attempted to make concessions — including an amendment that would have exempted businesses with fewer than 50 employees and another that would have mandated unpaid sick leave combined with new worker protections — but the bill still stalled.

He acknowledges that the voter-approved policy could be reversed by the Legislature. (Vargas’ eight-year run as a senator ended at the close of 2024.)

But he believes the fact that it passed so overwhelmingly signifies support from not only Nebraska workers, but business owners as well.

Workers’ access to paid sick leave is on the rise

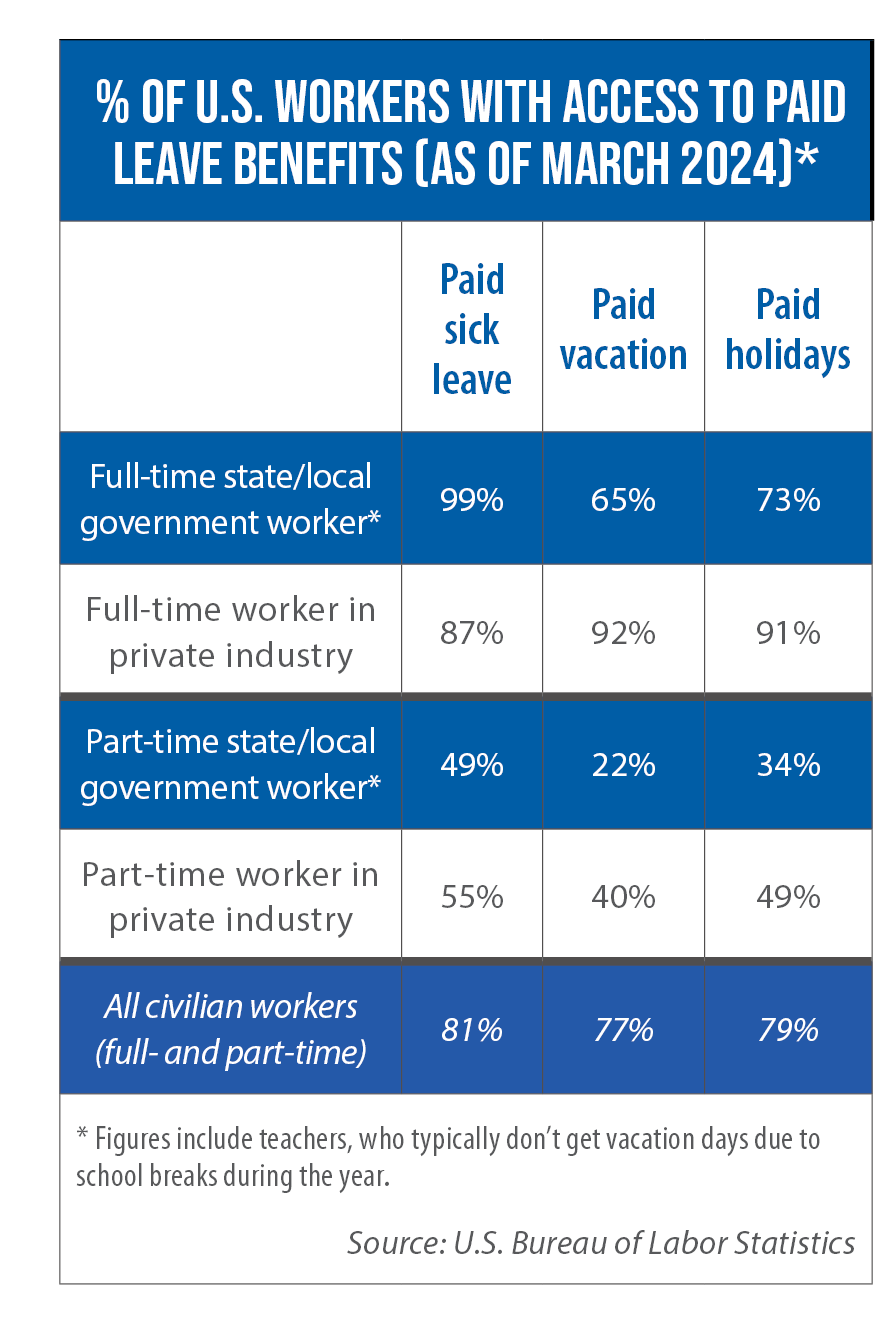

In early 2024, the IZA Institute of Labor Economics released a policy paper that summarized past research on paid sick leave while examining the impacts on employer costs and the effects of state mandates. Among the results reported in that paper:

- “Employees without access to sick pay are less likely to undergo mammographies, Pap tests and endoscopies at recommended intervals.”

- The estimated cost for employers providing paid sick leave is 41 cents per hour, according to the institute’s analysis of data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- State-level mandates result in an increase of 13 percentage points in the “coverage rate”: employees who have access to paid sick leave.

Other recent research produced by IZA found mandated paid sick leave reduced rates of influenza-like illness by an average of 11 percent in the first year (relative to states without mandates) as the frequency of working-while-sick dropped.

Eighteen U.S. states now have laws requiring paid sick leave for workers.

But Dr. Nicolas Ziebarth of the ZEW Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research says mandates are not the only reason for a recent increase in access to paid sick leave. The rate of U.S. workers with sick pay jumped from 64 percent in 2015 to 78 percent in 2023, Ziebarth’s research shows. That’s in part because more employers saw value in offering the benefit.

“They could attract better workers, retain workers, and it’s not extremely costly,” Ziebarth notes.

In terms of the link between paid sick leave and workforce participation, Ziebarth points to a 2024 study. It analyzed female employment in three states with mandatory paid sick leave: California, Massachusetts and Oregon. The study concluded that the mandates increased rates of employment by around two percentage points, with the largest gains occurring among women without a postsecondary degree and women who are Black or Latina.

How paid sick leave became a court battle in Michigan

Michigan was the first state in the Midwest with mandatory paid sick leave for workers.

In 2018, a citizen-initiated ballot initiative sought to guarantee paid sick leave for every worker in the state (excluding federal workers). Under that proposal, individuals who worked for small businesses (fewer than 10 employees) could accrue 40 hours of leave in a 12-month period, and those who worked in larger establishments could accrue 72 hours.

But this proposal never made it to the ballot in Michigan.

Instead, lawmakers took up the measure. Their final enacted bill (SB 1175) differed from the proposed ballot initiative in several ways.

For example, the law exempts additional categories of workers and only applies to employers with 50 or more workers. Additionally, the Legislature’s version changed how many hours in paid sick leave that a worker at larger-sized businesses must be able to earn over the course of a year: It’s 40 hours, instead of the 72 hours called for in the ballot proposal.

The Michigan Supreme Court ruled in 2024 that the original standards outlined in the ballot initiative must take effect in late February, even though it never appeared on ballots. The justices ruled that the Legislature had acted unconstitutionally by changing the ballot language and enacting a different version.

‘Tension’ in labor law

Following the court’s ruling, Sen. Thomas Albert filed SB 992, which would allow for a continued exemption for Michigan’s small-business owners. For Albert, too, another major point of concern with the pending new mandate on paid sick leave is what he refers to as a “no call, no show” clause.

Under the original ballot measure language, individuals using paid sick leave for an unforeseeable purpose do not need to provide their employer with multi-day advanced notice or documentation unless their leave lasts longer than three consecutive days.

“It’s really disruptive,” Albert says. “When you look at labor law, there’s always this tension of, ‘How do we have a balance of what’s proper protections for employees, and then also making sure employers can keep their businesses operating?’ ”

Albert also points to a survey conducted this summer by the Small Business Association of Michigan. Even without a state mandate, 79 percent of responding small businesses said they were offering workers paid time off.

Like other states, Michigan’s mandate on paid sick leave also covers individuals needing to take off work as the result of domestic violence or sexual assault. This time off can help victims cooperate with law enforcement or access rape-related health treatment. Supporters of the new mandate in Michigan argue this ability should be guaranteed to all workers, regardless of business size.

Details on state laws in Midwest

ILLINOIS

- 1 hour of paid time off for every 40 hours worked

- Annual accrual of 40 hours of paid leave

- Workers do not need to give a reason for the time off

MICHIGAN

- 1 hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked

- Annual accrual of 40 hours of paid sick leave for workers at small businesses (fewer than 10 employees) and 72 hours for workers at larger establishments

MINNESOTA

- Paid sick leave: 1 hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked; annual accrual of 48 hours of paid sick leave

- Paid family and medical leave: Workers receive 12 weeks of partially paid family or medical leave or a combination of the two not exceeding 20 weeks. Benefits are financed through payroll deductions on wages. Employers must pay at least half of the premium.

NEBRASKA

- 1 hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours worked

- Annual accrual of 40 hours of paid sick leave for workers at small businesses (fewer than 20 employees) and 56 hours for workers at larger establishments